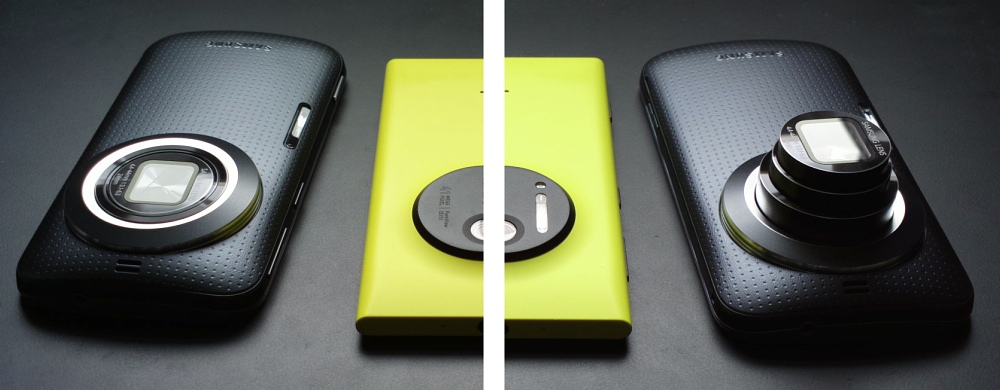

(From left to right, staggered – the Nokia 808 PureView (Symbian), the Samsung Galaxy Z Koom (Android), the Nokia Lumia 1020 (Windows Phone), the Nokia N93i (Symbian S60), the Samsung G810 (Symbian S60))

Simply ‘zooming’ with an old fashioned camera phone means horrible ‘blocky’ results, of course – we’ve all seen them. A 2MP (say, this was 2005 or so, after all) camera was ‘zoomed’ and all that happened was that existing sensor pixel detail was blown up to encompass more than one pixel in the final image, i.e. the zooming process didn’t reveal any new image information, it was simply taking pixel level detail and making it larger, warts and all.

Optical part 1

In fact, results were so terrible that most commentators, at the time, simply decried digital zoom as the spawn of the devil and told users to avoid it like the plague. And rightly so, though there’s a twist in this tale in recent years, as we’ll see below. The first to innovate were Nokia’s engineers (a common theme in this smartphone imaging world), with the Nokia N93 and N93i (in the photo above), with a transformer design, based around a huge central barrel, in which was housed a genuine 3x optical zoom and (for the time) a decent sized sensor. The result was sensational 3MP images, with the user zooming in as required before pressing the big circular shutter button. All of a sudden you could capture photos at events (etc.) that weren’t previously possible (on a phone).

Samsung had a go too (yes, they used to be in the Symbian world, back in the day), with the G810 shown, building a 3x optical zoom into a more traditional phone body, albeit at the expense of a very thick phone and with a smaller sensor. The G810 never got sold to the mainstream (making mine extremely rare!) but it turned out to be a bit of a lemon because of a characteristic of optical zoom that the N93 also suffered from to a degree.

The sealed optical zoom module in the Samsung G810, from 2008…

Downsides and the dawn of PureView

You see, as with any optical zoom, as the multi-element lens system is tracked in, zooming the image, the amount of light that’s allowed in reduces drastically – think of a corridor that’s narrowing in aperture, with the result that, when zoomed in, unless you were starting with plenty of light, results were often digitally noisy and unpleasant, especially with 2006/7 sensors. Additionally, the camera units were complex and costly, as you’d expect. Which is why two Finnish engineers at Nokia, on a business trip to Tokyo, came up with the idea of a simpler, part optical, part digital, zoom system, using a large 41MP sensor and traditional auto-focus optics, but using software to extract the required image, up to 3x zoomed, algorithmically, from the high resolution sensor.

It took a while to perfect the technology though – famously, up to five years, until 2012 before the Nokia 808 ‘PureView’ was ready. Using the existing Symbian platform as a base, a dedicated imaging chip was used to do all the real time oversampling and interpolation that was needed to pull off the zooming trick. And not only for stills but for video too, i.e. mimicking what you’d get if you had optical zoom, except without any reduction in the aperture through which light was needed to arrive. In other words, even when the camera was zoomed by 3x, each sensor pixel in use (effectively the central region of the 41MP sensor) was still receiving just as much light as when no zoom at all was used.

This, along with the physically simpler and more durable optical design, meant that the Nokia 808 PureView became the gold standard in smartphone imaging, and specifically zooming. The following year saw a version of the same camera, slightly slimmed, on a more modern platform, in the shape of the Lumia 1020. Although there were some compromises from the loss of a little sensor real estate (1/1.2″ down to 1/1.5″) and from the loss of the dedicated imaging processor, the zoom functionality remained. And, in fact, worked even better on the 1020 because of the use of a better sensor technology and the addition of another new element – OIS.

The 1/1.5″, 41MP camera module from the Lumia 1020, shown here as is, then the OIS mechanism for adjusting the optics, then a cut-through of the optics stack, and finally the huge sensor, laid bare.

OIS, Optical Image Stabilisation, is even more important when talking about zoom than when considering normal snaps, since when you’re zoomed in by 3x, every hand wobble is effectively magnified by the same amount. You can see this by looking at the viewfinder on-screen while zoomed in on the Nokia 808 or N93, for example. And, when shooting video especially, all these wobbles are captured for posterity. OIS means that any device wobbles are compensated for in real time by adjusting the exact angle of the optics, hundreds of times a second – meaning that you can have longer exposure for zoomed stills and that zoomed video footage is beautifully smooth, almost as if shot on a tripod.

Optical part 2

The system worked so well that it has been copied a few times by competitors, though not quite on the same scale – Sony’s Xperia Z3 and Z5 range, for example, proclaim 8MP ‘supersampled’ ‘superior’ shots from an underlying 20 or 23MP sensor. Samsung though, did return – for the most striking of the products in the group shots here – to experimenting with true optical zoom, though this time round they got round the problems with miniature mechanisms by re-using existing telescopic zoom hardware from their standalone cameras. Even here, Samsung was limited, in its S4 Zoom and K Zoom products, because of the nature of ‘optical’, in that the zoomed light tunnel was constrained enough that they had to go with a relatively small (by 808 and 1020 standards) 1/2.3″ sensor. This ultimately limited the quality of the images in adverse conditions, though the K Zoom in particular was something of a favourite of mine, despite its other, related issues.

You see, in addition to performance problems with optical zoom, there’s also the matter, if implemented with a telescopic, multi-part, exposed mechanism, as on the K Zoom shown here, of durability, and specifically dust resistance. You’ll notice that the N93 and G810’s optical zooms were all contained within a sealed glass environment – the S4 Zoom and K Zoom were vulnerable to dust getting into the optics and onto the sensor – with resulting ‘blobs’ and shadows creeping into images. Google it – it’s a real ‘thing’ with these devices, sadly.

The Samsung Galaxy K Zoom, shown retracted and extended, besides a Lumia 1020: the physical difference between high resolution software zoom and optical zoom clearly demonstrated

So the high megapixel super-cropping zoom solution from Nokia is the best we’ve currently got? Just about, it’s physically simple and works well, though both the 808 and even the Lumia 1020 are now effectively obsolete, meaning that we’re stuck with the 20MP sensors and 2x zoom on the likes of the Lumia 930 and 1520.

Interpolative zoom

Yet the world and expectations have moved on slightly – whereas a ‘pure’, and quite possible 3x zoomed image was quite acceptable at 5MP, we’re now seeing that resolution on even front facing cameras and most rear facing cameras are up in the 13MP-16MP region. Giving little wiggle room in resolution for any kind of competitive software zooming. But I wanted to give a shout out to a modern image processing technique, as used first properly in the likes of the Galaxy Note 4 (in my tests, though plenty of flagships have followed suit since).

You see, it’s already a tough job taking R(ed), G(green) or B(lue) data from adjacent sensor pixels and combining them using a ‘Bayer Filter‘ to produce a meaningful full colour image. There’s already a healthy degree of guesswork going on inside the software to make sure that colours and details are as accurate as they can be – and most top phone cameras now do an amazing job. But the latest algorithms go further, not only Bayer filtering but also interpolating detail between the sub-pixels when required (e.g. when digital zooming). So on a 16MP flagship camera, a user can now use digital zoom by 2x and the end result is cleaner and more finely detailed than we have any reason to suspect. Yes, a lot of the data at pixel level in the final JPG is actually ‘made up’, i.e. pure guesswork, but the software is now so clever that the eye and brain are fooled into thinking that zoom magic really is happening.

Just a side note: beyond simply making your distant subject seem ‘bigger’, zooming has other benefits, whichever technology is being used:

- You can see better what you’re shooting on the phone screen

- The algorithms in the phone Camera software can better focus

- Ditto for getting a better light reading for the subject and auto-adjusting exposure and shutter speed

The purist in me would rather have genuine optical zoom, but I accept the physical limitations. Next in line, I’d rather have the 41MP PureView zoom in a durable, light-friendly solid state form, yet I accept that non manufacturer is currently doing this. And they’re not bothering because of my last point above – superfast imaging chips and super-clever software are regularly producing zoomed rabbits out of hats on phones like the iPhone 6 and Galaxy S6 ranges.

The future

Next up is the Lumia 950 range, of course, from Microsoft, with 20MP sensors but ‘next generation’ oversampling/OIS and PureView zoom. I’m expecting 2x true lossless zoom into the sensor and then another 2x interpolated zoom in the chipset and its software. Giving, overall, a genuinely useable 4x zoom yet in a phone body that’s less than 9mm thick. And that’s stunning. It’s been a fascinating journey, hasn’t it?

PS. Industry watchers may have spotted the launch and then delay over production of the Asus Zenfone Zoom, using a G810/N93-like miniature optical zoom that wraps light through two right angles in its journey to the sensor – I’m really not surprised that this hasn’t appeared yet – even with 2015 sensors and technology, physics dictates that there’s just not going to be enough light to go round in terms of capturing photos which are perceived to be good enough by modern standards.

PPS. I haven’t forgotten about the Lumia 1020’s ‘Zoom later’/reframing approach, either. But this is something slightly different and (ahem) the article’s long enough already!